ДОСТУП ОТКРЫТ

|

Switch to Russian |

Hunters have a concept called "offhand". It means that a hunter has to hit a suddenly appearing target by quickly raising his gun (that is, without aiming).

So, grammar knowledge is only valuable when a student can use it "offhand", as there's not a second between a thought and the phrase that expresses that thought, and there's no time to compute the harmony algebraically, like Pushkin's Salieri, let alone that the "music" suffers in the process.

The focus shifts from the topic of conversation to grammar, and speech becomes colorless, like that of a robot. Let's make a "sketch from life" to see how the "offhand" principle works in real life.

In a suburban English camp near Moscow, the most common question that everyone asked each other on the go was, “Have you seen Sasha (Julia, Masha)?”. What came out of the kids' mouths (having studied English for several years) when they didn’t "construct" the phrase, but genuinely wanted to know if I had seen Sasha? The most frequent was the Present Simple: “Do you see Sasha?”, and the second, after my remark “Your grammar!”, meaning they weren't quite "offhand", was the Past Simple: “Did you see…?”.

The correct phrase, "Have you seen" (Present Perfect), wasn't used by anyone. And try accusing these kids of not knowing the Present Perfect! Wake any of them up in the middle of the night, and they’ll recite the rule flawlessly, and they won't make mistakes on a test! What were they missing to apply their knowledge in real life? Was it the quantity of exercises that hadn't turned into quality? No, the reason was different.

The same symptoms have the same root cause: they all started learning the language with Present Simple. Therefore, it came to mind first. They drilled it with hundreds of “dead” exercises, and the worst part is, they started reading stories in which, supposedly for convenience, the narration was in Present Simple. After words like “one day, suddenly, then”, they saw and pronounced Present Simple! This wasn’t even a herbarium! In a sense, they were deceived!

Remember the fairy tale where a husband, trying to trick his talkative wife, hung loaves on a fir tree, and she believed that's where they grew? Yes, there's a special, rare occasion when Present Simple is used after these words (like when commentating a football match, or summarizing a book or movie), but the kids read a normal story: “One day he went..., he saw..., he said..., suddenly he heard...” and yet it went “One day he goes”. Essentially, their sense of time was knocked out from under them, making all subsequent exercises comparing tenses redundant.

- So, what should be done to ensure the correct tense comes naturally at the right moment?

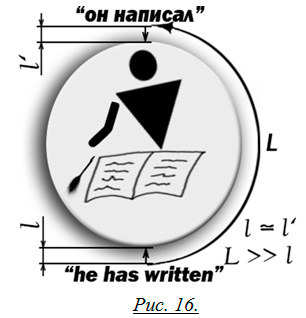

We've already used the botanical analogy of a flower in a field for a word, and this isn't coincidental. In Fig. 8, the concept of a "disk in the sky" was conveyed through the word "sun", so any grammatical phenomenon is also a concept, defined by one or several words, be it continuous tense or comparative degree. All the reasoning about "thinking indirectly", "tunneling through" can then be repeated regarding a grammatical phenomenon. The essence is absolutely the same: To think in a language, you need to instantly, via a short tunnel, transfer the thought from the object (grammatical phenomenon) to a correctly constructed phrase.

This illustration may differ from the previous one perhaps only in an even greater difference between the length of the tunnel and the bypass arc (Fig. 16).

So, let's dig the tunnels! We start by introducing a grammatical phenomenon through a natural situation, staging a mini-play with the participation of students. There isn't a grammatical phenomenon that can't be applied to a classroom situation using only each other and a small set of objects.

In Fitzgerald's story "Veronica's Hair," a young socialite gives advice to her provincial cousin: to hold a gentleman's attention, one should not deviate in conversation from the themes of "You, me, us together."

Let's take advantage of this advice. Of course, one can practice grammatical phenomena by discussing London's architecture or Australia's wildlife, but the theme "You, me, us together" is more relatable and comprehensible. For practicing a grammatical phenomenon, the vocabulary should be as simple and clear as possible; it shouldn't burden the structure of the phrase. Much like how fruits weigh down the branches of a tree, because it is the structure (these branches) that is the focus of the student's attention.

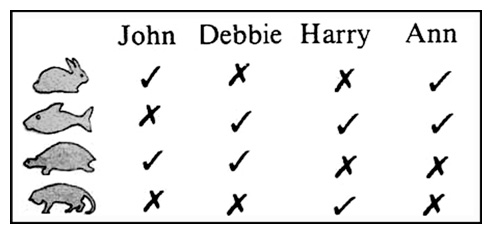

For example, the construction “I’ve got a … and a …, but I haven’t got a … or…” can be practiced using a table.

- I’ve got a rabbit and a tortoise, but I haven’t got a goldfish or a cat.

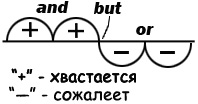

Intonation structure of a sentence:

A table is a decent option for practicing structure, but still not the best one, because the drawn cats and dogs don't meow and bark next to us, and you can't touch them. What can we come up with for such a situation? It's very simple! We only need four items: a textbook, a notebook, a pen, and a pencil. We play a game: we subtract 2 out of 4 items in such a way as to create a feeling of discomfort, a lack (intonation of regret), and we play out dialogues:

- I have got a book and a practice book, but I haven’t got a pen or a pencil.

Well, for Comparative and Superlative situations, you can compare each other and objects as much as you want. In the case of tenses, you can endlessly manipulate only the concepts of "Did - didn't do", "You said you would write this exercise next time". Conditional sentence: "if you had listened carefully, we would have had time to sing a song, etc."...

ДОСТУП ОТКРЫТ