|

Switch to Russian |

There's one boy named Ovik who is 9 years old (a real boy from Zhulebino, Moscow). At the age of 3 he went to the kindergarten, knowing zero words in Russian. Nowadays Ovik is fluent in Russian. As they say, he took the command of the language, he speaks without a slightest thing of accent even though his family still uses Armenian to speak daily. When asked a question of what language is easier for him to speak, he was very surprised and said: "Well...both languages are effortless to me!"

Dear reader! If among your friends there is a child from a super-special school or kindergarten who, having started learning the language at the age of 3, will say the same thing about English at the age of 9, then I will pay my respects to his teacher, quit working on my method and run over there in order to learn. Alas! Such schools do not exist!

So, what has happened to Ovik? There are thousands of people like him - an ordinary bilingual child. And yet, how did he do it?

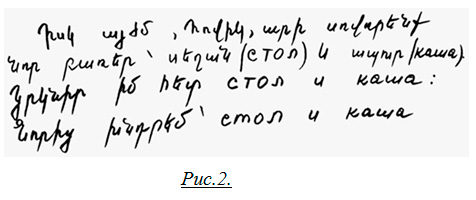

Let's go six years back and imagine this scenario: a 3-year-old Ovik enters the kindergarten. There's a teacher by his side who's holding his hand (just to comfort the kid while they are exposed to the new environment). The teacher is Armenian, but she teaches Russian while dividing her Russian speech into syllables (pic. 2).

*(Translation: "And now, Ovik, let's learn new words "table and porridge". Repeat after me: table, porridge")

Isn't it funny? Well, it's even funnier if we speak about the sounds being produced. Now let's swap Armenian to Russian and Russian to English. The result we'll see is an ironic picture of the method of teaching English according to the traditional methods. However, why is it ironic if there is no exaggeration? That is a direct display of a part of the lesson. It is easy to predict that in such a situation, neither the "table" nor the "porridge" will get stuck in Ovik's head. Well, how did it happen in reality? The Russian-speaking teacher while clapping her hands, intoned: "Kids, sit down to table! The porridge is getting cold!". At the same time, the table and porridge are visible and tangible. Also, the porridge smells delicious, so it's being imprinted in memory by association to what kids' taste buds sense. Plus there's vocabulary and grammar in a said sentence which starts to stick in mind. The word "Table", for example, sounded in the accusative case, together with the preposition "for".

- Well, yes, but this phrase could not define the concepts of "table" and "porridge"!

Quite right, but it was only the first exposure to getting to know the word. Not only that the words are not remembered, but also do not really define the concepts corresponding to them if they are said once with minimum context. After being dropped those words should grow (just as seeds do) while being used in different situations, gathering more context. For example:

-"What a delicious porridge!",

-"Eat the porridge, otherwise you won't have enough strength!",

-"This is not your table, Ovik!",

-"There's your table, by the window!",

-"Don't rest your elbows on the table!",

- So, the child studied the language absolutely without translation?

Of course, the same way they studied their native language at the time. Let us have a breakthrough and make the main goal of the program:

To bring up "English-speaking Oviks". Let's say the goal is to do it before they turn 15.

So, that's the goal, everything else will be the means of getting there.

Ovik studied Russian absolutely without an interpreter. And what language was your child born with? What do you mean "with none"? What language did you use to translate from, introducing new words into their vocabulary? You used the signs, facial expressions, visual images while empowering your speech with intonation.

Let's look at the simplest algorithm for defining concepts.

Step_1: I'm holding a green apple in my hand and I'm saying:

-This is a green apple. What have I said? That this apple is green? Maybe. Or maybe something like "I really want to eat."

Step_2: I'm taking a red apple in my other hand and I'm saying:

-This is a red apple.

About 50 percent of the children have already identified both the word apple and the colors, but still it was possible to understand it in another way. For example: "This is a gift from grandma, and this is a gift from grandpa".

Step_3: Transfer the colors to other objects, for example to a red pencil and a green book.

-This is a red pencil.

-This is a green book.

The colors have been determined.

Step_4: Let's show an apple among other fruits while naming them:

-This is a pear.

-This is an orange

-This is an apple.

The word "gift" is unlikely to get associated with a pear and an orange. Thus, we have also defined the word "apple".

The advantages of using this algorithm over saying a simple statement of the useless fact "an apple is an apple" are obvious:

1) The perception of the information through abstract concepts and visual images suggests that the process of its assimilation occurs at a subconscious level (just the case when we manage to distract a child from the thought of learning a language).

2) In this case, we manage to do without an intermediary language (translation into Russian), which greatly simplifies the process of assimilation of the information.

3) Such an approach allows the child to "guess" themselves, which obviously makes the information received more meaningful.

4) The process of extracting the information obtained this way occurs quicker, since the child will compare the visual image directly with the word "apple" at the right moment(again without switching to the intermediary language), which means that the information received will not be "useless" in memory.

However, such an algorithm is too dry, strict, primitive, and we use it only in cases when an unfamiliar word is the key in a game (song, fairy tale) and it slows down understanding the speech in general. During the lesson, these steps are more vague, as in the case of Ovik. It all happens while narrating something, without distracting from the point, since the goal is not to learn new words at all. Again, the child hears a word in different contexts, as if highlighting the subject from different sides, begins to understand its meaning, while memorizing it at the same time.

Imagine that you are looking through a herbarium. There is an inscription in Latin under the dried chamomile ... Another option: you went out into the field and saw daisies growing around, and along the way received a lot of additional information about this flower (the color, the smell, the soil that it grows in). Also you've captured many other flowers, herbs, the sky, the sun with your peripheral vision. The same happens to the word, like a flower, it grows each on its own ground, in its own environment, and before we pull it out and dry it under a press, we will observe it like a flower in a field.

A fragment from a seminar for colleagues (but not for students).

I'm holding a pencil in my hand.

-This is a pencil. What can I do about it? I can write with it, I can drop it, I can break it … but I have no idea, how I can learn it.

In fact, have you tried "learning a pencil"? Let's define the concept of "learn".

- Well, for example, it means to leave a word in memory, along with its sound, spelling and meaning.

Ok, let's use this definition, but let's clarify for what period of time did you store this information in memory? For your whole life? – That’s too perfect! Sometimes people forget the name of their beloved nephew, who was separated by fate for many years. For a year? For a month? Maybe, until Monday, until the third lesson, when the teacher will test you on your new vocabulary? It's pretty funny, isn't it? Why don't you keep them instead of keeping them in mind till Monday. In addition, the learned list of words has almost no relation to the language, just like individual notes to music.

Picture it, you have decided to learn an aria from an opera, but you've decided to learn all the notes separately. How many are there? Quite a bit! If we speak about a range of two octaves and chromaticisms, modulations, their number is 7x2 = 14 (white keys) + 5x2 = 10 (black ones). The total is <= 24. Now, let's step to the piano. We will sing each one as many times as it occurs in the aria (to be sure): "G-G-G" (28 times), "D-flat" (17 times)...well, now, sing the whole aria! Didn't work out? Why is that? It's because music is not a set of notes, but those invisible threads that connect them together.

- Well, this concerns the words, but what about dialogues, poems, stories? Don't you have to learn them by heart, too?

It's a little different here, because this information, unlike the word, has a meaning, an emotional background. You can compare a poem to a musical piece that we perform from memory. Now let's see how the child retells a dialogue or a story. Pay attention to the places where they stumble, what is the brain working on? Is it working on the construction of a phrase? – This should happen easily, automatically, the grammar is responsible for this. Maybe on the order of the presentation? Are we loading the brain with unnecessary information, such as

- what exactly did Masha eat?

- what time did Sasha get up?

- where did Dasha go?

Exactly. Look: the child is trying to remember a sequence of actions, facts, events that have nothing to do with language.

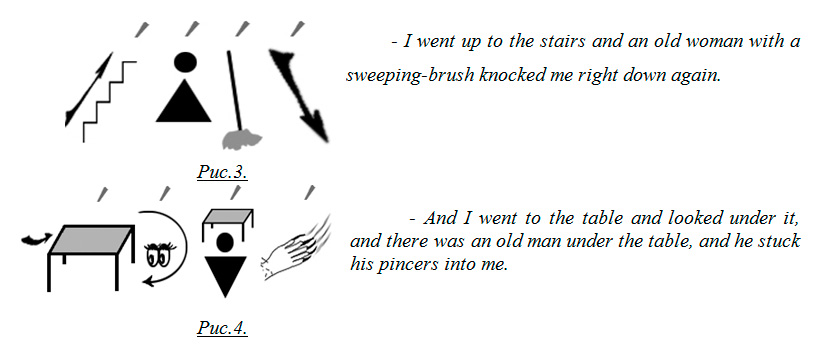

Imagine such a situation: When asked how you spent your vacation (in your native language), you hold a long speech, like a report, in one breath, without stopping. There's something unnatural about it, isn't there? But this is exactly what we ask to get from a student when we force him to retell a text or his topic, like “My holiday”, as in this case. In real life, our speech is like firewood, it needs stimulating answers, comments, questions from another person. It is also convenient for us to tell a story based on photos taken on vacation, you are just commenting on them. It's the same for kids. It's easier for them to speak while having some pictures to speak about. Even if you don't have pictures, try using your imagination, you will definitely paint a picture. For example, in "Jack and his friends" fairy tale, which we staged, the robber, ran onto the stage and even out of breath shouted rather long sentences, which we drew on the board as follows:

There are four accents in each sentence, four semantic accents, four locomotives that drag wagons of words behind them. By the way, the parts were remembered instantly.

(* Here and further we use fairy tales from the collections of “English folk Tales” and “Fairy Tales of Britain” by Iris Press.)

When learning a poem, aiming to memorize it, we, of course, repeat it several times, we set different tasks for the child, except memorization. For example, we change the character of a cat (insidious or cunning), achieve credibility by making the kid move. If it does not occur to the child that THIS is the process of memorizing a poem by heart, then this poem will be learned easily and quickly. Of course, at the same time, we intonate each phrase as vividly as possible, listening the music of speech.

- But if speech is music, then where can I get notes for it?

What an interesting question. Indeed, any musical phrase can be written within five lines, and everyone, even a beginner in music, can correctly, though not very musically, play or solfage it. And how do you know where to raise your voice, where to lower it, where to speed up the pace, where to slow down, and where to pause (and how) in colloquial speech? The thing is that dramatic hearing is a much more subtle, incomprehensible thing, and develops much more difficult, oddly enough, than musical hearing, because there is no single melody for the same phrase. Each actor “sings” his own way, coming up with his own melody. Another thing is that this melody can be brilliant when it touches your soul, fascinates you. For example, as in fairy tales voiced by wonderful actors such as O. Tabakov and J. Yakovlev. The melody of speech can also be too simple and even ... fake when you just don't believe the speaker, when you blackout, fall asleep listening to a tedious lecturer. And here is the key word – “believe". This single word that became a criterion thanks to Stanislavskiy ("I don't believe") is able to unveil the secret of speaking with the correct intonation and the gist of the communicative method.

Now let's see how it works during the lesson. I would call it a kind of test light bulb that is on throughout the lesson, glowing a calm green color, and flashes red every time the signal stands for “I don't believe".

Example (“Come with me"):

"Let's go" structure is worked out while using the vocabulary:

Park, disco, cinema... (one of the first lessons).

A student has to invite the teacher or a friend to the park or to the disco... etc..

"Let's go to the disco..."

Mind that in case the student says the phrase clearly, loudly, looks at the opponent...but not in the eyes, you ask the rest of the kids: "Do you believe him/her?" - and they immediately shout: "No! I don't". Subsequently, every one of them, “like Stanislavsky himself,” often says himself, criticizing a friend: “I don't believe you (her/him).” The correct version of this "inviting" phrase should literally tear you away from the chair, and if you feel it, you should accept the thrown ball and "get involved".

-Yes, good idea!

I love dancing!

I'm crazy about it!

Where do you want to go?

Also this phrase may make you want to express disagreement:

-Sorry!

I don't feel like dancing!

I’m in a mood for sitting around and watching TV!

An example ("say it to make their mouths water"):

At a later stage, when a child tells someone something, for example, about a city, he should do it the way the announcers do in travel programs, so that the listener has a burning desire to lay out the last money they have and go there… Just like Pushkin wrote: “If I'm alive, I'll visit a wonderful island.” In other words, it should be told “to make your mouth water".

...There was a scene in some old movie: the boss was reading the recipe of some dish. He does it once, twice, three times, and when his colleague says “enough is enough, and it's good on itself”, the boss answers: “no, it's necessary to make your mouth water”! I made this quote from the film the criterion for all narrative retellings.

However, we must immediately mention the special requirements for the text. If it is written absolutely “without taste”, such as: the year of foundation of the city, the population, the list of factories, museums, etc., then this material is obviously unsuitable for teaching by the communicative method.

- And what do we do in this case?

There's nothing to do! Put it aside and take another text! Such texts are generally written for some unreal person, because if a guide told you about the city in your native language like this, you simply wouldn't listen to him.

So, the Stanislavsky criterion is not turned off throughout the lesson. We all have to believe each other, no matter what we say, and therefore, play truthfully.

- Yes, but then it turns out that everyone, both children and teachers should be actors. But what if they are not?

Now I'm not going to believe you here. “All the world’s the stage, And all the men and women are merely players.” as the great Shakespeare said, and he was absolutely right. This is the saying that T. N. Ignatova took as the epigraph to her book “English for communication".

Even the most phlegmatic, strict, unemotional person will not utter the phrase “I'm so tired, I want to sleep insanely!” with the intonation of a robot. They will sigh, yawn, mutter this phrase, emotionally color it, in other words, play it.

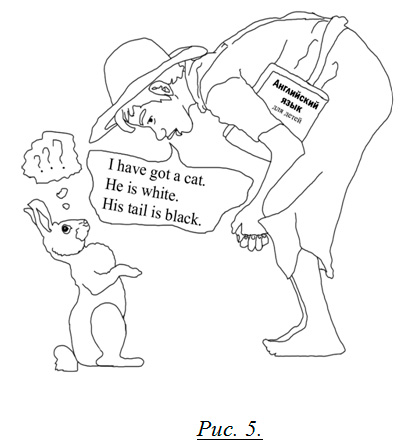

Listen to how a child tells their peers about their kitten. They do it super excitedly, the eyes sparkle: “And my mother brought me a kitten yesterday!!! It's soooo small, fluuufly, it's so white, but its' tail is black..." And now let's compare it with the intonation of a student commenting on the topic “My Pet".

- I've got a cat. He is white. His tail is black.

There's a kind of exhale (period) at the end of each phrase. The student is just stating the fact, however there are many English poems about cats and dogs that you can stage, as if trying to make others “believe”, hugging a toy to yourself, just excitedly staging a make-believe play.

For example,

I love my little pussy

Her coat is so warm.

And if I don’t hurt her

She’ll do me no harm.

By the way, when we torture a child by forcing him to squeeze out sentences when retelling something, we also cause great harm to other children in the group by forcing them to listen to this parody of language, because one of the basic rules of the communicative methodology categorically prohibits a student from listening to incorrect speech, it's just like a young musician listening to a wrong a melody or singing.

The student is strictly forbidden to listen to wrong speech!

- Does this contradict the previously mentioned Chukovsky principle of “Oink” and “Peep”?

Aren't we cutting down the freedom of the student with those over-demanding tasks to speak correctly?

Well, firstly, we have such conversations about the wrong melody and the parody on speech with you strictly among ourselves, keeping it a secret. It's not meant for the ears of our students. Secondly, if you succeed in managing, directing the child's speech correctly, giving the correct signal, then the child will start saying short but well thought out sentences.

So, if we make knowing that every child is a natural actor a law (as I look at it, studying in different theatrical schools/colleges is nothing more than getting adults back to their childhood, so they forget all the boarders or formalities), then maybe teachers must go through acting training in order to be successful at holding classes according to our communicative method.

“You may not be an associate professor, but you have to be an actor!” - That's what I would say about any teacher in any field! Even such “dry” subjects as mathematics and physics need acting animation! I remember the bright lecturers of MEPhI, who “brought the knowledge to life " with their acting manner, made complex formulas “talk”, magnetic fields “to be felt ", neutrons and protons “visible”! And I'm grateful to them!

- And how to determine the "degree of readiness" of a teacher?

Say the phrase “Where is my pen?". If you are really looking for a pen, the children will try to help you by scanning the table with their eyes. Ask “What time is it?” and see if your friend looked at the clock. If they did, then they believe you, which means you're acting correctly. But don't get artistry confused with eccentricity, hysteria, with constant bouncing and screaming. The thing is being too active all the time will tire any audience even though you might be the best actor or a musician. And, by the way, the brightest color in speech is SP (subito piano – a sudden departure for a quiet sound). While speaking you can say the word "suddenly" using SP.

Each new unit should be introduced through the performance of such a mini-play: for example, if your goal is to work out prepositions, you can pretend that you have lost a pen and are looking for it

- under the chair,

- on the table,

- behind a book

- and maybe it rolled somewhere between the lockers?

- Oh, yes, I've put it in my bag!

[Any parts of the lesson held in Russian should be perceived as conditionally translated for better understanding by readers who do not speak the language. In fact, the entire lesson should be exclusively in the language that's being studied!]

Mind that all that act should be murmured, as if you're talking to yourself! You'd better not use the unnatural to this situation loud, clear speech!

Nothing kills a language like an edifying intonation!!! (The most common mistake), because doing it like that we are supposedly trying to “hammer” something into the child (“so it gets remembered quicker”), alas, getting the opposite effect. According to the traditional methods the phrases like "Sit down, please! Open your book!" are used to communicate with students. They call such phrases "commands". So, the teacher is made to use a "commanding voice" unintentionally. In order to feel how fake they sound, let's mentally translate them into Russian or (the same thing) look at yourself through the eyes of an Englishman. Would you be able to say it the same way: “SIT-DO-WN-PLE-ASE! OP-EN YO-UR-BO-OK!"? Probably, this is not how it looks in a real-life situation, but a bit easier or calmer.

Nothing kills a language like an edifying intonation!

Dear colleagues and parents! We are more likely to be able to deceive each other than to deceive a child! Each of them has an ultra-sensitive lie detector in their heads, and the slightest falseness in our intonation will immediately cause a reaction of “I don't believe”! Having clogged our memory with such false, “dead” information, we later wonder why, having met a “real-life” Englishman, we do not understand their speech and cannot express our thoughts quickly and correctly. Imagine that you put a dirty, crumpled shirt in the closet, and then, running away to work, you snatch it out and are horrified that you can't leave the house wearing it. But you put it there yourself! Absolutely the same thing happens with language. Why on earth should “dead” words and phrases be embedded in someone's memory and then “come to life” in a real-life situation?

- Well, so how do you teach a child a “real-life” language from the very first stage?

Here is one of the techniques.